Men

Men, 2005

Mixed media, DVDs: Smashing door, 6.50 mins, looped. Smashing car, 8.50 mins, looped

Exhibited: Westspace Inc, Melbourne, May 2005

Architect/Building referenced:

Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret. Villa Savoye. Poissy-sur-Seine, near Paris, France, 1928–31

Glenn Walls

Men

Video installation, wood, plastic, lights

2005

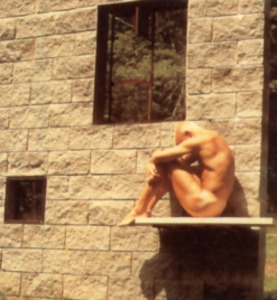

Queer space is not always safe space. To illustrate this I created the work Men (2005) that was exhibited at Westspace Inc, Melbourne, in May of that year. The installation consists of a scaled-down version of the left-hand side of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye (1928–31). The work was constructed out of wood and painted white. The pillars were constructed out of PVC piping. Contained in the front-first floor window was a monitor displaying a DVD of a male attacking an interior door with an axe. At the rear, on the ground floor where the garage would be, was placed another monitor displaying a DVD of a male smashing up a car.

The two videos contained in this work were filmed at separate locations. The car smashing video consists of a car sourced from a car dealership for the purpose of destroying it for the installation.[1] Filmed in a private garage and using a professional actor, this video was shot in one sequence. The camera was placed on a tripod and did not move during filming. The footage originally running for 3 minutes and 20 seconds was slowed down to run for 8 minutes and 35 seconds. The purpose of this was to emphasise the destruction taking place in the interior. The footage was then looped in video-editing program Final Cut Pro, enabling it to be on constant repeat while the work was on exhibition.

The door-smashing video was filmed on location in my studio in Melbourne. A set was constructed to give the appearance of a minimal white interior, similar to the interior of the Villa Savoye. Again using a professional actor, the video was shot in one sequence with the camera located in one position. The footage was slowed down to run for 6 minutes and 50 seconds, again emphasising the destruction taking place, looped and on constant repeat during the exhibition.

In this work I sought to create an aspect of queer life relating to same-sex domestic violence that is hidden in the built environment. Same-sex domestic violence has only recently become a focus of the gay and lesbian community of Australia. Lee Vickers cites Island and Letellier’s definition: ‘any unwanted physical force, psychological abuse, material or property damage inflicted by one man on another’ (Vickers 1996). Vickers estimates that 15–20 per cent of gay and lesbian couples are affected by domestic violence.

Wayne Myslik in his article ‘Renegotiating the Social/Sexual Identities of Places’ explains: ‘By exhibiting a degree of social control by the gay community, queer spaces create the perception of being “safe spaces”’ (Myslik 1996, p. 157). The reason to construct a concept of a ‘safe space’, Myslik argues, ‘is an important one for gay men, who are at risk of prejudice, discrimination and physical and verbal violence throughout their daily lives. Queer spaces are generally perceived as safe havens from this discrimination and violence’ (Myslik 1996, p. 157). Nevertheless these are usually public queer spaces such as a club or park. The hidden nature of queer space in the domestic setting allows domestic violence to occur out of public view.

Research conducted by the AIDS Council of NSW found ‘that many people within the gay and lesbian communities held beliefs that precluded an understanding of the power issues within domestic violence, ‘e.g. that women don’t perpetrate violence and men aren’t victims of domestic violence or that same sex domestic violence is a fight between equals’ (Gray 2005). The same research also found that many gays and lesbians had limited understanding of what was happening to them and terminology to describe it. This was partly due to the belief that domestic violence only happened in the heterosexual world and that the advertising campaigns in the media used language and images unrelated to their circumstances.

This lack of acknowledgement of gay domestic violence in the media became the basis for using Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye for the work Men. Designed for a couple and located around thirty kilometres from Paris, the structure’s white walls, controlled symmetrical geometrical forms and clean lines give it a clinical masculine/heterosexual appearance. My work provides an ironic twist to the Le Corbusier building whose structure offered an opportunity to exhibit a contemporary image of queer space by depicting queer males as ‘masculine’ through their actions and dress. The intention was to display a non-stereotyped image of queer life.

Within the structure Le Corbusier had designed a number of windows and viewing holes that were strategically placed in positions such as the top of ramps that gave viewers, as they ascended the ramp, a framed picture of the surrounding landscape. Le Corbusier states:

As one walks along, one can see how the architectural arrangement unfolds … a real promenade architecture which continuously opens up changing, unexpected and sometimes astonishing views. (Sydney eScholarship Repository: University of Sydney Library 2008)

The concept behind the design for Villa Savoye was that upon entering the structure the viewer would be pushed to peripheral, specialised locations to take in the view. Internal walls aided in the movement of the individual to these locations. To highlight the impact of same-sex domestic violence, videos were placed in the picture windows of this structure that was designed for contemplative viewing. The purpose was to emphasise this structure’s capacity to display same- sex domestic violence to the outside world. If the idea behind Le Corbusier’ picture window was to give a sense of the landscape always being in motion, then the idea behind this video installation was to reverse that notion by allowing the viewer of the work to view domestic violence normally conducted away from public view.

Le Corbusier’s publicity shots for the Villa Savoye are not presented with images of occupancy. Many of these images only show traces of human activity with items left casually about. However, these items were always male, a coat, a hat, a pair of glasses. The public presentation of these images maintained the masculine/heterosexual hierarchy of the structure. Through the placement of videos related to same-sex domestic violence the masculinity of the structure is not called into question, however, the sexuality of the structure is reconfigured.

The use of the white wall and large flat symmetrical surfaces presented in the Villa Savoye gives it an air of calmness, logic and masculine superiority. I believe this environment is intended to project a structured life. My project was to break the heterosexuality presented in this building and bring forth an issue rarely mentioned in either the straight or the gay media. The violence portrayed is intended to contradict not only the calmness of the building, but also the belief that gay men are not violent. The violent acts not only destroy the objects in this structure, but also destroy the contemplative space of this building for the pursuit of rational, ordered living. The windows in this case are not used to frame a calming landscape in which one sees, but are used to frame the destruction that is being seen.

In the work of artist Mark Robbins the notion of creating a view of the landscape through window frames is evident. In his work Utopian Prospect (1988) Robbins produces a structure that is not enclosed, but provides viewing holes in which one sees the activities on the other side. The outdoor work is situated in Woodstock, New York, on the grounds of the Byrdcliffe Art Colony. Unlike Villa Savoye, which is an enclosed space, Robbins’ work is an open space consisting of one brick wall with window frames that intersects with the sloping site. A small brick tower supporting a swinging vane is situated metres from the wall. Robbin uses the wall and its viewing holes to implicate the activity of seeing without creating an enclosed space. Patricia C. Phillips states:

Robbins’ ‘Utopian Prospect’ constructs the quixotic time of vision rather than an unyielding space of the view. The wall is an implication of – rather than an obstruction to – the experience of active seeing. Unlike the controlled space of the traditional viewing pavilion, the open space of Robbins’ project is about watching others see so that the landscape is experienced fully through one’s own eyes and the imaginative references of others’ encounters. (Phillips 1992, p. 10)

In the video installation Men, the spectator is located in the landscape viewing the activities through the window frames of the wall. The Le Corbusier building, Villa Savoye and Robbins’ Utopian Prospect provide architecture with the potential of seeing and the creation of a narrative. Both use materials in their construction, such as concrete and bricks that are typically associated with control, regularity and power linked to gender stereotypes. The difference between the two works is that Robbins’ installation places the viewer in the landscape viewing through the framed window back into the landscape. The viewer does not enter the interior of the structure. As Robbins’ work is not an enclosed space, it is much more difficult to control and manipulate what the spectator sees. As Phillips states, ‘Robbins’ eloquent, oppositional work is an optimistic prospect for the potential of vision for seeing what it is we really desire and require from architecture’ (Phillips 1992, p. 10). By choosing architecture that allows an element of the voyeuristic I was able to publicly display aspects of life to others.

Mark Robbiins Mark Robbins

Utopian Prospect Utopian Prospect

Installation, bricks, wood, steel Installation, bricks, wood, steel

1988 1988

[1] This video can be viewed at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4OD0dEouTU

Books

Betsky, A 1997, Queer space: architecture and same-sex desire, William Morrow & Co: New York.

Colomina, B 1996, Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture as Mass Media, MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass.

Friedman, TA 1996, ‘Domestic Differences: Edith Farnsworth, Mies van der Rohe, and the Gendered Body’, in Reed, C (ed.) 1996, Not At Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Architecture, Thames & Hudson: London.

Friedman, TA 2006, Women and the Making of the Modern Home; A Social and Architectural History, Harry N. Abrams, Inc, New York.

Isenstadt, S 2006, The Modern American House: Spaciousness and Middle Class Identity, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; New York.

Island, D and Letellier, P 1991, Men Who Beat the Men Who Love Them: Battered Gay Men and Domestic Violence, Harrington Park Press, New York.

Reed, C (ed.) 1996, Not at Home: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Architecture, Thames & Hudson: London.

Robbins, M 1992, Angles of Incidence, Princeton Architectural Press Inc: New York.

Sanders, J 2004, Joel Sanders: Writings and Projects, Monacelli Press: New York.

Spector, N 1995, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Guggenheim Museum: New York.

Vandenberg, M 2003, Farnsworth House: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Phaidon Press: London.

Chapters of books

Myslik, DW 1996, ‘Renegotiating the Social/Sexual Identities of Places: Gay communities as safe havens or sites of resistance?’, in Duncan, N (ed.), Bodyspace, Destabilizing geographies of gender and sexuality, Routledge.,

Phillips, PC 1992, ‘Prospect for Architecture,’ in Robbins, M (ed.), Angles of Incidence, Princeton Architectural Press Inc.

Websites

Collins, G 1990, Portraitist’s Romp Through Art History, New York Times, viewed 2 March 2009, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE6D6113AF932A35751C0A966958260

Sydney eScholarship Repository 2008, University of Sydney Library, viewed 16 December 2008, http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/3815

Gray, B 2005, There’s no Pride in Domestic Violence: Gay and Lesbian Community Awareness Campaign, viewed 28 May 2008, http://www.glhv.org.au/node/199

Philip Johnson 2005, Telegraph.com.uk, viewed 16 December 2008, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1482161/Philip-Johnson.html

Vickers, L 1996, The Second Closet: Domestic Violence in Lesbian and Gay Relationships: A Western Australian Perspective, E LAW: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law, viewed 28 May 2008, http://www.murdoch.edu.au/elaw/issues/v3n4/vickers.html